The Disability Support System, Part 2

Second Half of Chapter 5, The Money Chapter

Hi all! Ian is away at a summer program at an autism college for the summer, so I’m cruising through book writing. I have about 40,000 words now with a goal of 60,000 words. I’m done with Chapter 5 and working on Chapter 6. Chug, chug, chug.

This is the second half of chapter 5, which gives some basic instructions for parents about filling out the paperwork. I published the first half last week.

A recent report found that 225,333 students (ages 3-21) in New Jersey currently have IEPs, but only 26,726 individuals (ages 21-100) are currently receiving DDD payments. We don’t know how many adults who formerly had IEPs are employed and don’t need DDD. We don’t know if people aren’t getting DDD services because they couldn’t finish the paperwork or because they are gainful employed. But the huge difference in numbers is indicative of a problem.

I hope everyone is having a great summer! Webinars start up again in the fall. No paywall today.

Second Part of Chapter 5

What can you do with SSI money?

At the end of the SSI process, a disabled adult will receive around $600 per month, if he lives with his parents. He’ll receive about another $300 per month, if he’s living alone or parents charge him rent. Funds will go directly to the individual, not the parents. In one year, that comes to $7,200.

Set up a bank account in your child’s name, which can be accessed by you. The government will send the funds directly to the bank. Checks arrive bimonthly with no paperwork. The good news is that you’ll probably never speak to a government official again. Yes, it was hell getting into the system, but once you’re in, everything just happens automatically unless funds exceed limits or the individual no longer needs help.

Your young adult should get a debit card to spend their funds. A debit card will provide records of expenditures, which can be shared with the government in case of an audit. It’s also a useful way for your young adult to learn how to purchase small items for themselves around town and gain independence. It’s good for them to spend money in little ways without having to ask you for a hand-out.

With your name on the account, you can monitor the account to make sure that your child hasn’t overdrawn the account and has spent enough. Your child can never have more than $2,000 in that account or in any bank account, while receiving SSI. If their savings exceed $2,000, your child could lose all their benefits.

We all know that it’s very expensive to raise a child with special needs, so spending that $600 monthly check is a breeze. Just make sure that you spend that money in the right way to avoid any conflicts with SSI. They shouldn’t be using that money to buy groceries for the entire family every month. The funds are supposed to be for personal use. Other examples of appropriate usage of SSI money:

Appropriate expenses:

Food (lunch at the mall, Saturday night tacos, Trader Joe’s frozen meals),

medical (the neurologist who doesn’t take your insurance, speech therapy),

educational (a class at the community college, books),

clothes (new jeans at Old Navy, sneakers on Amazon),

personal items (one video game per month, a Lego set, a new puzzle),

entertainment (movie tickets, a trip to a video arcade).

Inappropriate expenses:

a fur coat for Grandma

a gas grill for Uncle Don

a case of red wine and a pack of cigarettes

a subscription to the adult movie channel

SSI to Medicaid to the States

Getting SSI is a HUGE amount of work for only $7,200 per year. Why should we do that? Because SSI is just the first step in this process, and there are more benefits to come.

You groaned. Yes, you did. I heard you. The good news is that SSI is the hardest part. If you made it through SSI, then you’re likely to make it through to the end.

The next step is painless. In most states, by completing the SSI application, you automatically qualify for Medicaid. A few states have another step in the process, but it’s a quick step. Why bother with Medicaid when you already have health insurance for your child through your job? Hint: It’s not about the health insurance.

Medicaid1 is a joint federal and state program that helps cover medical costs for some people with limited income and resources. It’s different from Medicare, which is the federal medical insurance program for older citizens. Medicaid also sends a block grant to the states to support disabled people who qualified for SSI. The states use that Medicaid money, along with their own funds, to provide an essential safety net for the disabled people in their states.

The United States is a federal system of government with a national system of government that loosely governs 50 states; some issues, like national security, are completely controlled at the national level. Other issues, like education, are mostly controlled by the state governments.

When it comes to disability issues, the federal government is involved only at that first step with SSI. When that’s done, the states take over. The SSI process is the same for everyone in this country. At the state level, there are fifty different disability systems; some states have harder paperwork, other states provide more money. Because I can’t describe all fifty state disability programs in one book, I’ll give some general overviews and share examples from my home state of New Jersey.

While you may rarely use Medicaid to pay for your child’s doctor’s bills, it is actually the biggest driver of your child’s benefits. Yet, you may never deal with Medicaid itself, because their role is invisible. They hand funds to the states, and then the states takes over.

State Systems

Once you have received SSI and Medicaid, it’s time to start the state paperwork. Most states won’t even let you start the process without having proof that you qualified first with the federal government. State benefits begin at age 21, but you can start the paperwork process at any time after you finished with SSI. You should start everything at the latest by age 20, so the disability benefits will start promptly on your child’s 21st birthday.

Believe or not, you will have to prove to a whole new group of bureaucrats that your young person is disabled. You’ll answer the same questions and spend another year on duplicate paperwork. The good news is that you’re now a pro. When you fill out the state paperwork, you’ll follow the same principles that we discussed for SSI. Describe your child on their worst day. Imagine them alone in a strange hotel room. Imagine them at work in McDonald’s without any help.

Every state handles their disability system differently. Some are more generous than others. Some states, like New Jersey, have multiple different departments within the state government supporting disabled adults. Here in New Jersey, The Department for Developmental Disabilities (DDD) distributes federal medicaid money at age 21. The Department of Labor might provide internships at Stop and Shop, while The Department of Human Services provides extra help for individuals with medical issues. Yes, you have to apply to each department for funding.

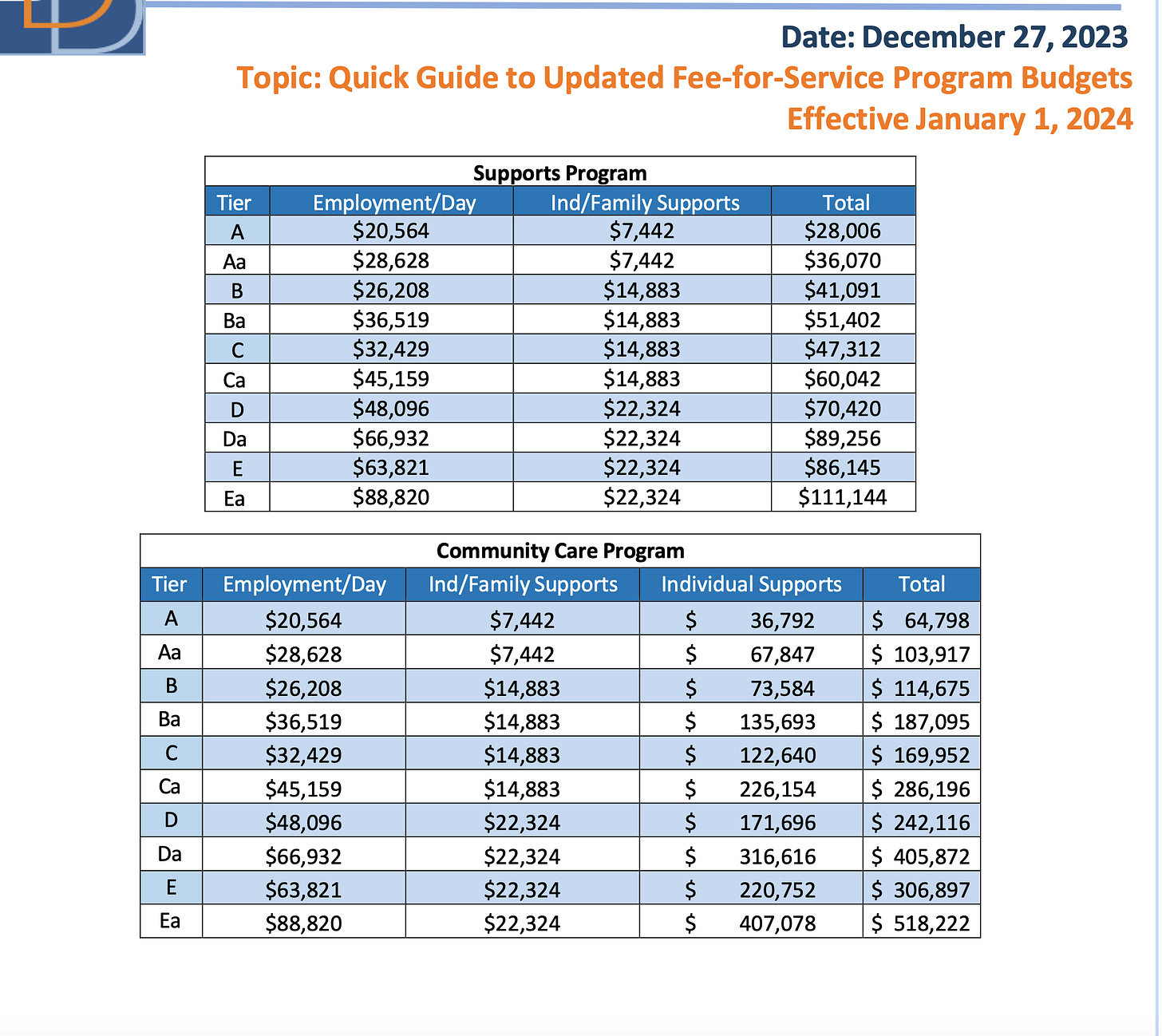

Like SSI, we have a written form to complete in New Jersey. The NJCAT2 is 35 pages long with 61 questions. Unlike SSI, it’s all multiple choice with no short answers. State workers compile the answers to NJCAT to determine eligibility and then assign the individual a tier based on the level of disability. People with mild issues are assigned Tier A and have a budget of around $30,000. Those with the most needs are assigned Tier Ea with a budget of around $111,000. There’s a wait list for individuals, who need housing and other supports in the state’s Community Care Program, which offers significant help.

Spending the State Money

Depending on several variables — your state, your ability to care for your adult-child, and your adult-child’s level of disability — the state could prove anywhere between $30,000 and $500,000 to help care for the individual. While the SSI money goes directly to the individual, state disability money in New Jersey goes first to a Service Coordination company. These are private companies that are approved by the state to help you find appropriate ways to spend the disability money.

Once you’ve got your child into the system, you will choose a company that will supervise your child and their services. Network with more knowledgeable parents and interview the companies to find the business that works well with you. That company will assign you a service coordinator, who will complete the necessary paperwork from the state and help you find appropriate services.

So, let’s pause for a minute to think about the trickle of money. It comes from the federal government through Medicaid, then it goes to the state, from there to a service coordination company, and then with your support coordinator, you’ll decide if that money should go to a day program, exercise program at the Y, or directly to you. Another third party will write the checks. The money takes a long trip before it actually benefits your child.

Yes, you can pay yourself for being a Direct Service Provider for your child. If your child doesn’t fit in well in the available local day programs and you have the energy to manage his time, then you can do all that and then pay yourself. A lot of us are already doing that job of driving our kids to therapy, managing their health needs, and arranging group activities with other local families. Now, you’ll get paid for that time.

To become a Direct Service Provider in New Jersey, I had to get CPR training and watch some training videos. I complete paperwork every two weeks and keep track of my hours. It’s a hassle, but a small one. Frankly, once public education ends, if your child does not attend a full time day program, you’ll be busy. Their day needs to be filled with a mixture of work, volunteer activities, and recreation. You’ll be finding those programs, doing all the driving, and waiting around. That’s a full time job, and the state will now pay you for that work.

The service coordinator can also directly compensate private companies and outside agencies to provide a service to your child, like a day program provider or an approved therapist. About $5,000 of my son’s state funds goes directly to a private tutoring service that teaches him computer programming skills. I never see a bill for that. My son is on a waitlist to get funding for housing, because I would like him to live in a community aimed at adults with low support needs. I regularly attend “Transition Fairs” at the local community college, where various small businesses that were approved by the state, advertise themselves to parents. One company might provide transportation for disabled people. Another might do job training. If I like a group, and they fit into my budget, my service coordinator will line up those services for my son.

Extra Credit: 529s and Able Accounts

SSI and the state’s disability system are the primary sources of funding for services that protect disabled adults. But parents have a few other tools in their tool box.

Many parents in our country set up 529 account3s when their children are born to save money for college. A 529 is a tax-advantaged savings account designed to be used for the beneficiary's education expenses. Money is automatically deducted from a paycheck after taxes. As long as the money stays in the account, no income taxes will be due on earnings. When you take money out to pay for qualified education expenses, those withdrawals may be federal income tax-free—and, in many cases, free of state tax too.

Parents may set up these accounts long before their children are diagnosed with autism. Parents probably don’t know whether or not their disabled child with attend college, so they’ll keep funding those accounts. After 18 years, a considerable sum may have accrued in these accounts for their children, who might never be able to attend a traditional college.

The good news is that a 529 money won’t affect their child’s eligibility for SSI. These account are usually in the parents’ name, so those funds do not have to be declared during the SSI process. Still, parents have to figure out how to use those funds without taking a huge penalty.

Depending on your state, 529 money can only be used for an accredited college — not an option for every autistic young adult. Parents can’t use that money for other post-high school educational options, like transition programs, day programs, and job training programs. If money is withdrawn from a 529 for a non-approved use, those funds are subject to taxes and a ten percent penalty.

Parents with disabled children can take around $18,000 from a 529 account annually and put it into an ABLE4 account, another kind of tax-advantageous savings account for disabled people. $18,000 isn’t a whole lot of money, when parents have saved for 18 years for their child to go to Harvard. With as much as $300,000 in a 529 account, parents would have to make that transfer to an ABLE account annually for 16 years to access those funds without taking a penalty. Some parents tell me that the transfer from the 529 to an ABLE account happens easily and without excessive paperwork.

Some non-profit organizations for the disabled community recommend that parents do not use the ABLE accounts to hold 529 money5. Rather, parents should show their state that their child has a disability, so the state can waive the ten percent penalty for withdrawal of funds for non-college purposes. Unused 529 money6 can also be used in other ways, including for funding another child’s education, saving college money for a grandchild, and rolling over $35,000 into a Roth IRA. But there’s no consensus on the best way to use 529 funds.

The main purpose of an ABLE account is to enable beneficiaries to save up to $20,000 from a job annually, without losing their SSI benefits. Workers can save up to $100,000 with no disruption to their benefits with a $500,000 cap on the accounts. Keep in mind one big danger with these accounts — in some states, any money left in the ABLE account after the worker’s death will be given directly to Medicaid to compensate for services. Currently, 137,000 disabled Americans7 save money in ABLE accounts.

Hopefully, your young person can work, earn money, save a little money, and keep their benefits. Work gives all of us a purpose, a place to socialize, and a way to challenge ourselves. Nationally, 46 states have policies to help 400,000 disabled people get employed and keep out of poverty, according to a 2021 report by the Bipartisan Policy Center8.

New Jersey has a program called NJ Workability9 that enables workers to make as much as $76,332 per year without losing their benefits, and individuals can save up to $20,000 in an ABLE account per year. However, disabled workers say that the 7,000 individuals in the program are unfairly taxed10, so work still needs to be done to help disabled people work and retain essential supports that are only available through the disability system.

Is it Worth the Hassle?

It’s going to take almost two years to fill out the paperwork. Paperwork sucks. There’s a 50/50 shot that you’ll get rejected the first time around by SSI and then have to appeal the decision. Your kid has a lot of potential, and hopefully he’ll have a great job in the future. Even if your kid is unemployed, he just plays video games all day and doesn’t bother anyone. Is it worth going to the bother of filling in all this paperwork?

This is a personal decision. It depends on family resources, of course. Some families would rather spend their time together than bothering with paperwork nonsense. Others would rather see how their kids manage in the work world before they deal with the disability system. These are all perfectly rational decisions.

However, there are other good reasons to do the paperwork beyond the money. Once you get onboard onto the state system of disability, you’ll be assigned a service coordinator, who will help you find services for your young adult. They’ll line you up with appropriate exercise classes and social groups. They’ll connect you with mental health services and other therapists. This person should be your long term support system.

We also have to consider our ultimate demise. We’re all going to croak someday, and even if we’ve set up a special needs trust and a guardian, that may not be enough. If you and your spouse go down in a fiery plane wreck, the state will be able to care for your young adult immediately, if they are “in the system” If they aren’t in the system, then things will be more difficult.

I’ve heard horror stories of 60-year old autistic adults left alone in a house, when their 80-year old parents pass away. The state couldn’t come in immediately and set them up with special housing and other help, because there was no record of these individuals in the disability system. Yes, it’s tragic that those families never received any help from the government for all those years. It’s doubly tragic, when those adults are stranded for a month or more, while the state workers rush to complete the paperwork.

But families have to assess their own cost/benefits and do their own risk assessment. No judgments. This is a family decision, based on many individual factors. I hope that I have given you some tools to make a more informed decision.

2 https://www.nj.gov/humanservices/ddd/assets/documents/sample-njcat-assessment.pdf

4 https://www.mefa.org/blog/able-accounts-529-college-savings-plans

6 https://www.savingforcollege.com/article/5-ways-to-spend-leftover-529-plan-money

7 https://blog.ssa.gov/able-programs-prepare-for-expanded-eligibility/