At Age 22, My Son Is Getting His First Taste of College and Independence

And I'm having a meltdown

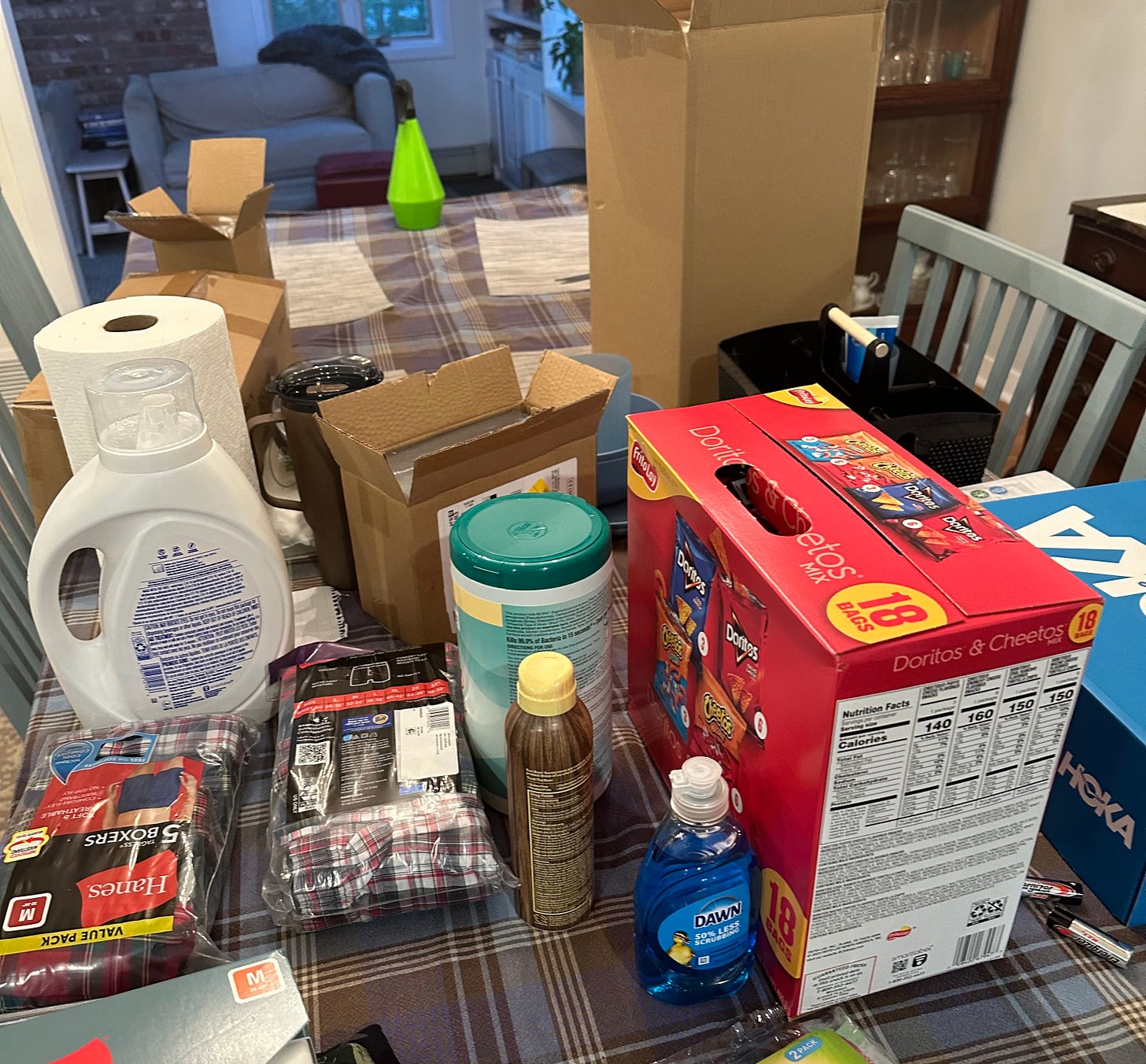

After a week of frenzied shopping on Amazon — desk lamp, window fan, desk organizer, storage bins, extra long dorm sheets — Ian and I settled into the serious business of packing him up for a five-week summer program at college.

We made stacks of shorts and t-shirts. We collected quarters for the washing machine. He made piles of devices, chargers, and Switch games. By Friday night, we had everything shoved into two large duffle bags and several boxes. It would all fit in the back of the Subaru with a little space for everyone’s overnight bags.

The next day, we headed north up to Putney, Vermont, so Ian could attend a five-week college bridge program at Landmark College. Landmark is one of two colleges in the country that are specifically for students with autism, ADHD, and learning disabilities. Going to college for the first time is a big deal for any kid. But for Ian, this college program is even more momentous, because it’s his first time away from home without us.

Inequities in Fun

Summer camps are often times when typical kids get their first taste of independence, but those camps aren’t an option for kids like ours. The typical camp counselors aren’t trained to understand autistic deficits; activities aren’t organized around toward autistic interests.

At town recreation programs, kids sit in the hot sun (sensory overload) and splash around with peers at the town pool (social skill deficits, unstructured time) — none of which is super fun for autistic kids. Private sleep-away camps offer more horrors like organized sports and theatrical productions. Shudder. Any camp with cellphone restrictions was unthinkable for Ian.

There are a handful of camps for kids with severe issues, like nonverbal autism and intellectual disabilities, but you can’t just toss all disabled kids into one program. So, some friends send their kids to typical camps and hope that they won’t get a dreaded phone call from the camp. “Uh… I think you need to come pick up Bobby… He’s refusing to get in the pool and insists on calling the other students, poopy-heads.”

One friend sent her son off to a boy scout camp in the woods in North Carolina, and then booked a room at a local motel for two weeks just in case she got one of those dreaded phone calls.

Schools routinely organize various week-long trips and other adventures for students. Jonah went to Germany for ten days with his German language class in high school. Other kids at our school go to China, Italy, even Bali. Parents pay thousands to cover the expenses for their students and teachers, but the events are organized and sponsored by the local public school.

Kids like Ian do not have those same opportunities for overnight high school trips. Their teachers don’t even organize trips for them to go to the local bowling alley. When Ian was in sixth grade, the entire class spent two days at a campsite together for a bonding experience. Since they didn’t assign him an aide, Ian couldn’t go. The school was actually mad at me for insisting that he should still go to school and be educated on those two days, while the others were gone on their fabulous trip.

We all know how inequitable public school education is across the country — suburban kids get one type of education, and poor kids get another. But those inequities can even exist within the same school building. Typical kids get one type of education; special ed kids get another.

Before Jonah went to college, he had all those camp experiences and school opportunities. He also had sleep away opportunities just by having friends. There were sleepover parties all though middle school — God awful events filled with 4am, sugar-fueled water gun fights. In high school, friends invited Jonah on their bar mitzvah cruises and Prom weekends at the beach.

But kids with autism don’t have friend groups like that. So, they miss out here, too.

Without camps, high school activities, and friend groups, not only are autistic kids missing out on opportunities for independence, they also end up with a lot of free time on their hands. Parents try to fill up that time with therapy and social groups. Maybe they’ll organize their own bowling trips with one or two other parents of autistic kids. But mostly it’s just free time, when autistic kids stay in their room playing Minecraft for hours and hours, utterly dependent on their families for all human interactions.

New Opportunities

Because of structural fun inequities, my son made it to age 22 without leaving us, beyond a one-night sleepover at my folks’ house. There were simply no opportunities for him.

When the public school was ready to boot him out public education when high school was over, I put the breaks on that plan. I made them continue educating him until age 22, so he could continue to build skills and I could figure out the next plan. Public schools don’t provide families like ours with guidance counselors, so I had to do all that research on my own.

As part of my research, I discovered a range of college summer programs for autistic teens and young adults. These mini-college experiences give students a taste of college with the dorm experience. Some fill in educational gaps and teach social skills, so students can thrive at their next college. Others are non-academic and provide job skill training.

This spring, Ian and I filled out the application for the Summer Bridge program at Landmark College. It’s a full day program with social skills and self advocacy lessons in the morning. In the afternoon, they offer an intensive writing program. Every evening and weekend, the school provides optional social activities. Perfect. And after a tension-filled application process (his interview was mediocre), he got in. Woot!

I relished every moment of packing him up, because it sucks to miss out on a parenting experience that all the other moms are talking about. Sure, the other moms sent their kids to camp when they were 12, and Ian’s now 22, but I’m still happy that I finally got to do it. Damn it.

The campus itself is gorgeous. It looks like a real college, not some special ed knock-off. The other students looked like him, similar strengths and weaknesses. His new roommate kept his headphones on and continued to play his game, while we chatted with his parents. They have medical support, in case Ian has epilepsy issues. (Knock on wood that this won’t be necessary).

After we moved him in, we attended an assembly together and then we were instructed to kiss him goodbye. After a mandatory family selfie, he ran across the quad to join his classmates. Nervous and excited at the same time.

He was ready for this big step. I, on the other hand, am having issues. Because the school and the community have been largely absent from our lives for two decades, we’re more attached than other families. Every day, I drive Ian somewhere — therapy, a tutor, on a trip to visit grandma. Every day, I’ll cook an Ian-friendly dinner. If Steve and I attend a party on a Saturday night, then we’ll do something fun with Ian on the Sunday afternoon. On Sunday morning, we go to church and do the food shopping together. He’s my permanent sidekick.

I’m trying not to text him too many times, however I am currently tracking him on my cellphone. It’s somehow reassuring to know when he’s in class and when he’s eating lunch. At the same time, I’m relishing the uninterrupted writing time and the freedom to make weekend plans without considering him. I’m cooking all the foods that he hates for five weeks — fish, curries, brown rice, zucchini.

We pick him up in five weeks. After that, Steve and I will take our first vacation in 25 years without either boy. Jonah will watch Ian and the cat, while we go to Spain. Then Ian will start a full time Associates degree program at the local community college this fall. We’re all moving forward.

Families like ours have a different path than other families, so when we have these moments of celebration and wonder and growth, we appreciate the hell out of them.